So that's what Brett tastes like. One has to ask the question who in their right mind would add this wild yeast to their beer on purpose. The boys at Mikkeller have, but anybody familiar with the way these guys operate will not find this unusual. I was lucky enough to have the Mikkeller experience in Copenhagen at the European Beer Festival, which is where I picked up this bottle of It's Alight. As I said, a Brettanomyces strain was purposely added to this beer and the Brett character is clearly evident - its presence affects every aspect of the beer. It smells funky as hell, does not retain any kind of foam, and thanks to bottle conditioning is highly carbonated and almost painful to drink such is the level of fizz. All of this can be placed squarely at the feet of the wild yeast because it produces any number of pungent flavour compounds that the more familiar Saccharomyces cerevisiae do not indulge in. Also, the Brett has no problem chomping through the longer, more complex sugars that more traditional brewing strains leave alone to pad out the beer. Despite the pungent yeast flavours the hops do make a showing providing quite a kick of bitterness and a little zest. It is reminiscent of Orval in many ways, mainly with respect to the aggressive hopping, very high carbonation and a quenching dry finish, but at a modest 4.5% abv it'll make short work indeed of a dry throat and give a refreshing kick along the way.

So that's what Brett tastes like. One has to ask the question who in their right mind would add this wild yeast to their beer on purpose. The boys at Mikkeller have, but anybody familiar with the way these guys operate will not find this unusual. I was lucky enough to have the Mikkeller experience in Copenhagen at the European Beer Festival, which is where I picked up this bottle of It's Alight. As I said, a Brettanomyces strain was purposely added to this beer and the Brett character is clearly evident - its presence affects every aspect of the beer. It smells funky as hell, does not retain any kind of foam, and thanks to bottle conditioning is highly carbonated and almost painful to drink such is the level of fizz. All of this can be placed squarely at the feet of the wild yeast because it produces any number of pungent flavour compounds that the more familiar Saccharomyces cerevisiae do not indulge in. Also, the Brett has no problem chomping through the longer, more complex sugars that more traditional brewing strains leave alone to pad out the beer. Despite the pungent yeast flavours the hops do make a showing providing quite a kick of bitterness and a little zest. It is reminiscent of Orval in many ways, mainly with respect to the aggressive hopping, very high carbonation and a quenching dry finish, but at a modest 4.5% abv it'll make short work indeed of a dry throat and give a refreshing kick along the way.

Saturday, January 24, 2009

Brett, and no doubt about it

So that's what Brett tastes like. One has to ask the question who in their right mind would add this wild yeast to their beer on purpose. The boys at Mikkeller have, but anybody familiar with the way these guys operate will not find this unusual. I was lucky enough to have the Mikkeller experience in Copenhagen at the European Beer Festival, which is where I picked up this bottle of It's Alight. As I said, a Brettanomyces strain was purposely added to this beer and the Brett character is clearly evident - its presence affects every aspect of the beer. It smells funky as hell, does not retain any kind of foam, and thanks to bottle conditioning is highly carbonated and almost painful to drink such is the level of fizz. All of this can be placed squarely at the feet of the wild yeast because it produces any number of pungent flavour compounds that the more familiar Saccharomyces cerevisiae do not indulge in. Also, the Brett has no problem chomping through the longer, more complex sugars that more traditional brewing strains leave alone to pad out the beer. Despite the pungent yeast flavours the hops do make a showing providing quite a kick of bitterness and a little zest. It is reminiscent of Orval in many ways, mainly with respect to the aggressive hopping, very high carbonation and a quenching dry finish, but at a modest 4.5% abv it'll make short work indeed of a dry throat and give a refreshing kick along the way.

So that's what Brett tastes like. One has to ask the question who in their right mind would add this wild yeast to their beer on purpose. The boys at Mikkeller have, but anybody familiar with the way these guys operate will not find this unusual. I was lucky enough to have the Mikkeller experience in Copenhagen at the European Beer Festival, which is where I picked up this bottle of It's Alight. As I said, a Brettanomyces strain was purposely added to this beer and the Brett character is clearly evident - its presence affects every aspect of the beer. It smells funky as hell, does not retain any kind of foam, and thanks to bottle conditioning is highly carbonated and almost painful to drink such is the level of fizz. All of this can be placed squarely at the feet of the wild yeast because it produces any number of pungent flavour compounds that the more familiar Saccharomyces cerevisiae do not indulge in. Also, the Brett has no problem chomping through the longer, more complex sugars that more traditional brewing strains leave alone to pad out the beer. Despite the pungent yeast flavours the hops do make a showing providing quite a kick of bitterness and a little zest. It is reminiscent of Orval in many ways, mainly with respect to the aggressive hopping, very high carbonation and a quenching dry finish, but at a modest 4.5% abv it'll make short work indeed of a dry throat and give a refreshing kick along the way.

Tuesday, January 20, 2009

It's been done before

This is a strange beer but perhaps less strange to me than other people becaus e I have done this experiment before. Stone Cali-Belgique IPA is a curious mix of their standard IPA with the addition of a Belgian yeast strain. I managed to do something similar quite by accident a few years ago when I brewed a hop driven pale ale using Amarillo and accidentally pitched a packet of Saf Ale T58 instead of the far more suitable S05. Both the packets are pink you see, and I hurriedly grabbed the wrong one. The result was a very strange beer that I didn't really enjoy. Much the same can be said about this IPA. It is immensely bitter, which is no surprise considering it comes from the boys at Stone, but there is little in the way of hop aroma because the pungent flavours produced by the Belgian yeast strain dominate everything resulting in a very bitter, funky beer that tastes a bit like bread along with other flavours I can't define. Curiously this beer tastes of the off flavour that has plagued my own beer over the last few months. This revelation has given me a great deal to think about indeed.

e I have done this experiment before. Stone Cali-Belgique IPA is a curious mix of their standard IPA with the addition of a Belgian yeast strain. I managed to do something similar quite by accident a few years ago when I brewed a hop driven pale ale using Amarillo and accidentally pitched a packet of Saf Ale T58 instead of the far more suitable S05. Both the packets are pink you see, and I hurriedly grabbed the wrong one. The result was a very strange beer that I didn't really enjoy. Much the same can be said about this IPA. It is immensely bitter, which is no surprise considering it comes from the boys at Stone, but there is little in the way of hop aroma because the pungent flavours produced by the Belgian yeast strain dominate everything resulting in a very bitter, funky beer that tastes a bit like bread along with other flavours I can't define. Curiously this beer tastes of the off flavour that has plagued my own beer over the last few months. This revelation has given me a great deal to think about indeed.

e I have done this experiment before. Stone Cali-Belgique IPA is a curious mix of their standard IPA with the addition of a Belgian yeast strain. I managed to do something similar quite by accident a few years ago when I brewed a hop driven pale ale using Amarillo and accidentally pitched a packet of Saf Ale T58 instead of the far more suitable S05. Both the packets are pink you see, and I hurriedly grabbed the wrong one. The result was a very strange beer that I didn't really enjoy. Much the same can be said about this IPA. It is immensely bitter, which is no surprise considering it comes from the boys at Stone, but there is little in the way of hop aroma because the pungent flavours produced by the Belgian yeast strain dominate everything resulting in a very bitter, funky beer that tastes a bit like bread along with other flavours I can't define. Curiously this beer tastes of the off flavour that has plagued my own beer over the last few months. This revelation has given me a great deal to think about indeed.

e I have done this experiment before. Stone Cali-Belgique IPA is a curious mix of their standard IPA with the addition of a Belgian yeast strain. I managed to do something similar quite by accident a few years ago when I brewed a hop driven pale ale using Amarillo and accidentally pitched a packet of Saf Ale T58 instead of the far more suitable S05. Both the packets are pink you see, and I hurriedly grabbed the wrong one. The result was a very strange beer that I didn't really enjoy. Much the same can be said about this IPA. It is immensely bitter, which is no surprise considering it comes from the boys at Stone, but there is little in the way of hop aroma because the pungent flavours produced by the Belgian yeast strain dominate everything resulting in a very bitter, funky beer that tastes a bit like bread along with other flavours I can't define. Curiously this beer tastes of the off flavour that has plagued my own beer over the last few months. This revelation has given me a great deal to think about indeed.

Pilgrim's Progress

Last weekend saw another attempt to brew a straightforward ale. It looked a little like this:

Last weekend saw another attempt to brew a straightforward ale. It looked a little like this:4.6 kg Maris Otter

250g 120L crystal malt

Pilgrim 11.3% 60 mins

Willamette 4.4% 20, 10, 5, 0 mins

Mashed at 66 C

OG 12 Plato

Saf 05

This beer has a number of new elements; I have never used Pilgrim or Willamette before and look forward to see what kind of flavour they'll give the beer; I loaded the water with calcium sulphate and calcium chloride, bringing the the calcium concentration up to around 250ppm which will have aided the mash, break formation and the yeast in their work as well as adding fullness to the beer and enhancing hop character; finally I used my new wort chiller which proved very effective, dropping the temperature very rapidly initially but also got the wort to room temperature far quicker too. Along with this I tightened up just about everything else in the process to try and get a clean tasting beer. I'll keep you posted.

Sunday, January 18, 2009

A big ol' can of beer

I have spied this can of beer on my local supermarket shelf a number of times over the last year but relented for all sorts of reasons. Today I decided to buy it to wash down the juicy steak sandwich I had in mind for dinner. The can holds a litre of lager and is something of a novelty - to me at least. The sight of it is curious as is the sensation of holding it in the hand. It was dirt cheap too but sadly it let me down in its primary function with a nasty rubber like aftertaste. I was a little disappointed because I have tried this beer before from the bottle and it struck me as a solid if unremarkable German lager. I suppose I could look to the can as the cause of this unpleasant flavour, but cans are quite suitable for storing beer despite what is widely believed.

While I was in the mood to buy canned beer I grabbed some Newcastle Brown Ale. I last drank this many years ago and it wasn't as I remembered it at all. It comes across a

s very promising initially, looking pleasant enough and smelling quite complex in a fruity kind of way and seems like it is going to deliver some serious flavour, but then it disappears with a whimper and a nasty metallic tang. This metallic note is common enough in many English ales I find, and in the past I would

s very promising initially, looking pleasant enough and smelling quite complex in a fruity kind of way and seems like it is going to deliver some serious flavour, but then it disappears with a whimper and a nasty metallic tang. This metallic note is common enough in many English ales I find, and in the past I would have attributed it to the can.

have attributed it to the can.It wasn't just a short lived can fetish that made me try some Newkie Brown. Oz Clarke and James May found themselves in the Newcastle Brown Ale brewery during the latest episode of their boozy adventures and Oz wasn't impressed with the beer at all. I thought I would give it a try for myself and see what it was all about. Laura over at Aran Brew has mentioned the appearance of the ICB crowd in the book of the series, and we can expect to see them all on the television in the next few weeks. My Centennial Ale was picked as their preferred beer of the evening, thanks to The Beer Nut, and as a result has made it into the book too. I really would have put more care into the label if I knew it was to be published.

Thursday, January 15, 2009

Old School Extreme

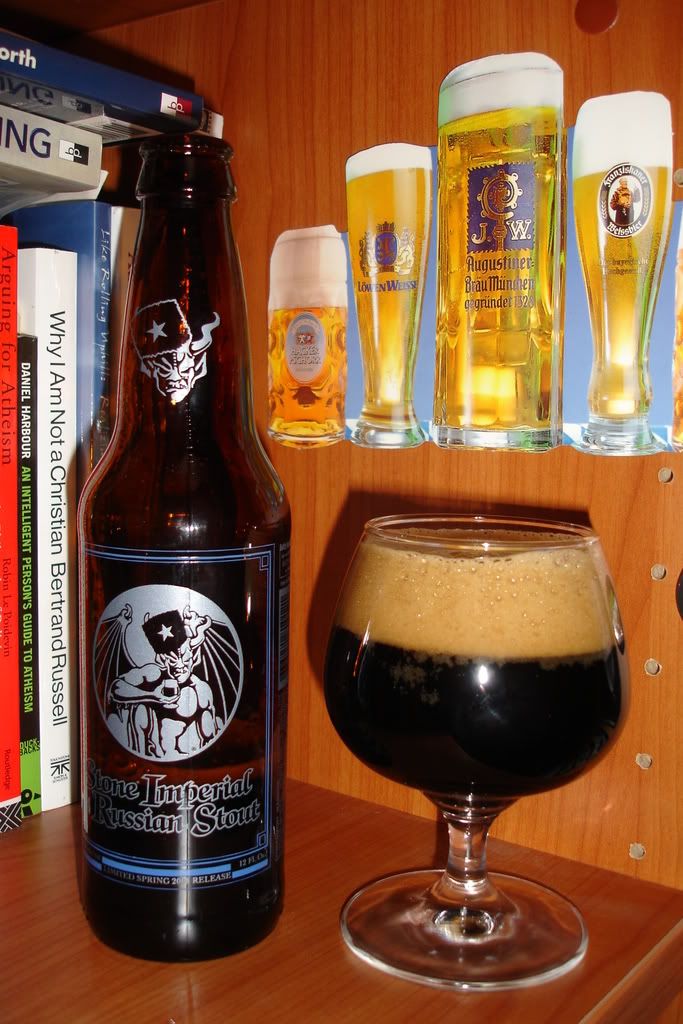

I enjoy comparing beer styles made by different breweries. It is interesting to see how individuals have chosen to interpret a particular style. This is never more enjoyable than comparing an English brewed beer with what an American brewer has decided to do with it. When you think about it, imperial stout is exactly what American brewers would love. It was extreme beer before beers became extreme. Standard strength IPAs were not enough for some American brewers and so imperial and double IPAs were concocted. Not so with Imperial stouts though. All they had to do was brew it as strong as they dared and more than likely it would be a perfect example of imperial stout because the uncompromising colour, flavour and alcohol content fits right in with the extreme brewing ethos.

I enjoy comparing beer styles made by different breweries. It is interesting to see how individuals have chosen to interpret a particular style. This is never more enjoyable than comparing an English brewed beer with what an American brewer has decided to do with it. When you think about it, imperial stout is exactly what American brewers would love. It was extreme beer before beers became extreme. Standard strength IPAs were not enough for some American brewers and so imperial and double IPAs were concocted. Not so with Imperial stouts though. All they had to do was brew it as strong as they dared and more than likely it would be a perfect example of imperial stout because the uncompromising colour, flavour and alcohol content fits right in with the extreme brewing ethos.Samuel Smith's Imperial Russian Stout is something of a tiddler in these stakes coming in at only 7.5%, but it doesn't disappoint on the flavour front with rich treacle on the nose that carries through into the mouth, supporting a pleasant fullness that is not overly viscous. It appears to be fairly well attenuated for a beer of its strength, not particularly bitter for a big stout and has the lovely velvet like roasted barley feel, but strangely I have experienced this to a greater degree in some stouts of normal strength. The carbonation is suitably low but still results in some satisfying foam cling to the glass at the end of it all.

Typically the American contender in tonight's events weighs in a little heavier at 10.8%. Stone Imperial Russian Stout is considerably more bitter, a great deal more viscous and amazingly, is impenetrable to light. Seriously. I held it up to the sixty watt bulb on my desk lamp and no light passed through. It's a black hole of a stout, sucking all light around it. It has little of the treacle flavour found in the English offering, instead giving up a small measure of the richer roast malt character that is typical of American dark beer. Coffee, liquorice and potent alcohol smack you on the nose, but it really comes to life after warming in the palm when a delightful spiciness develops. The Americans appear to have done it once again in the dark beer stakes. Someday a European dark beer will top them. I'd wager it'll come from Scandinavia.

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Unexplored potential

The potential is breathtaking. What you're looking at is 25 kg of some of the world's finest two row pale malt. Maris Otter, to those in the know. It is without form, ready for crafting into any number of fine beers. Crisp pale ale? Without doubt. Rich barley wine? Certainly. Smoked porter? Perhaps. Whatever takes my fancy. But my excitement is met by trepidation in equal measure. Sadly my brewing endeavours have not gone to plan over the last 6 months or so. I have ditched a hundred litres of beer because of a stubbornly persistent off flavour that I cannot shift.

The potential is breathtaking. What you're looking at is 25 kg of some of the world's finest two row pale malt. Maris Otter, to those in the know. It is without form, ready for crafting into any number of fine beers. Crisp pale ale? Without doubt. Rich barley wine? Certainly. Smoked porter? Perhaps. Whatever takes my fancy. But my excitement is met by trepidation in equal measure. Sadly my brewing endeavours have not gone to plan over the last 6 months or so. I have ditched a hundred litres of beer because of a stubbornly persistent off flavour that I cannot shift.Remember this ale? It was my return to the mash tun after a long break, and to be honest I was certain that it would be taint free thanks to a tightening of my brewing technique. Sadly it was not, so this is my next offensive against the nasty flavour; a new fully pimped home made wort chiller. It has far greater cooling capacity than my previous one and should cool things down far quicker and prevent me, through sheer impatience, from aerating the wort at too high a temperature. You see, my existing wort chiller takes an age to get wort down to room te

mperature. It'll drop the first fifty degrees centigrade very rapidly indeed which takes care of all my my cold break requirements, but I simply cannot wait the length of time required to get the wort down to 20 C. As a result of this, and other things peculiar to my brewing set up, the wort tends to get aerated at around 25 C and sometimes a little higher. My latest vexed theory is that this is oxidising my break filled wort and precipitating the pesky off flavour. This coming weekend should see the test of this theory, but in the meantime can any brewers out there let me know if they are impatient like me, or having greater brewing maturity, ensure that their wort is plenty cool before aeration?

mperature. It'll drop the first fifty degrees centigrade very rapidly indeed which takes care of all my my cold break requirements, but I simply cannot wait the length of time required to get the wort down to 20 C. As a result of this, and other things peculiar to my brewing set up, the wort tends to get aerated at around 25 C and sometimes a little higher. My latest vexed theory is that this is oxidising my break filled wort and precipitating the pesky off flavour. This coming weekend should see the test of this theory, but in the meantime can any brewers out there let me know if they are impatient like me, or having greater brewing maturity, ensure that their wort is plenty cool before aeration?

Sunday, January 11, 2009

Probably........not

I chanced upon some Guinness Mid Strength the other evening. I had heard it was about the city but wasn't terribly bothered in hunting it down because I imagined it wouldn't be worth the effort. It turns out I was right; it really isn't worth the effort. Even the effort of raising the pint to your face is wasted on this beer. It looks just like full strength Guinness and for the most part smells just like it too but everything goes wrong when it enters your mouth. It has no length whatsoever and is miserably watery.

At the same bar I was very interested to see a tap for Carlsberg Mid Strength. I didn't anticipate it at all but of course had to try some despite rarely drinking its full strength namesake. Once again things didn't quite work out, but it wasn't so bad because I am familiar with non alcoholic lagers such as Beck's Unleaded, and in a blind tasting I would say that this Carlsberg was in actual fact alcohol free rather than the 2.7% stated on the tap. It has the classic alcohol free taste that is shared also with Erdinger's isotonic excuse for a sports drink. Laughably the blurb on the beer mats scattered around the pub suggest that the mid strength tastes exactly the same as the full 4.2% Carlsberg. Absolutely ridiculous, but if anyone knows the power of advertising, it's the peddlers of mass produced bland lager. I think I'd prefer go alcohol free and drive home than sink a couple of pints of mid strength lager and run the lottery of a roadside breath test.

The experience was interesting to me for a number of reasons. Firstly it highlighted just what ethanol brings to two different and distinct beer styles and just how difficult it is to make a tasty low strength b eer when you are unwilling to up the malt or hops in order to add some character to the beer. Britain has any number of very tasty low alcohol ales, but they differ to this attempt by Guinness because session ales in Britain are designed to be tasty and low strength, while Guinness appeared to have merely removed the alcohol but left everything else much the same. Secondly it pissed me off that the mid strength was almost the very same price as full strength beer despite the reduction in excise that Guinness had to pay on the production of these beers. This is nothing new of course - a bottle of entirely alcohol free beer is the same price as normal beer in Irish pubs, but clearly Guinness have carried out expensive and extensive market research to establish a demand for this type of beer and perhaps might have considered making it a little cheaper to attract those who might be happy to drink this type of beer and drive home afterwards. Finally, despite the lack of satisfaction I derived from these beers, I am very happy to see them on the market. As I said, it is likely much market research pointed to a consumer demand for low strength beer, which is a wonderful thing as it can only inevitably lead to the availability of tasty bitters and mild in Ireland. Or maybe I'm just getting carried away.

eer when you are unwilling to up the malt or hops in order to add some character to the beer. Britain has any number of very tasty low alcohol ales, but they differ to this attempt by Guinness because session ales in Britain are designed to be tasty and low strength, while Guinness appeared to have merely removed the alcohol but left everything else much the same. Secondly it pissed me off that the mid strength was almost the very same price as full strength beer despite the reduction in excise that Guinness had to pay on the production of these beers. This is nothing new of course - a bottle of entirely alcohol free beer is the same price as normal beer in Irish pubs, but clearly Guinness have carried out expensive and extensive market research to establish a demand for this type of beer and perhaps might have considered making it a little cheaper to attract those who might be happy to drink this type of beer and drive home afterwards. Finally, despite the lack of satisfaction I derived from these beers, I am very happy to see them on the market. As I said, it is likely much market research pointed to a consumer demand for low strength beer, which is a wonderful thing as it can only inevitably lead to the availability of tasty bitters and mild in Ireland. Or maybe I'm just getting carried away.

At the same bar I was very interested to see a tap for Carlsberg Mid Strength. I didn't anticipate it at all but of course had to try some despite rarely drinking its full strength namesake. Once again things didn't quite work out, but it wasn't so bad because I am familiar with non alcoholic lagers such as Beck's Unleaded, and in a blind tasting I would say that this Carlsberg was in actual fact alcohol free rather than the 2.7% stated on the tap. It has the classic alcohol free taste that is shared also with Erdinger's isotonic excuse for a sports drink. Laughably the blurb on the beer mats scattered around the pub suggest that the mid strength tastes exactly the same as the full 4.2% Carlsberg. Absolutely ridiculous, but if anyone knows the power of advertising, it's the peddlers of mass produced bland lager. I think I'd prefer go alcohol free and drive home than sink a couple of pints of mid strength lager and run the lottery of a roadside breath test.

The experience was interesting to me for a number of reasons. Firstly it highlighted just what ethanol brings to two different and distinct beer styles and just how difficult it is to make a tasty low strength b

eer when you are unwilling to up the malt or hops in order to add some character to the beer. Britain has any number of very tasty low alcohol ales, but they differ to this attempt by Guinness because session ales in Britain are designed to be tasty and low strength, while Guinness appeared to have merely removed the alcohol but left everything else much the same. Secondly it pissed me off that the mid strength was almost the very same price as full strength beer despite the reduction in excise that Guinness had to pay on the production of these beers. This is nothing new of course - a bottle of entirely alcohol free beer is the same price as normal beer in Irish pubs, but clearly Guinness have carried out expensive and extensive market research to establish a demand for this type of beer and perhaps might have considered making it a little cheaper to attract those who might be happy to drink this type of beer and drive home afterwards. Finally, despite the lack of satisfaction I derived from these beers, I am very happy to see them on the market. As I said, it is likely much market research pointed to a consumer demand for low strength beer, which is a wonderful thing as it can only inevitably lead to the availability of tasty bitters and mild in Ireland. Or maybe I'm just getting carried away.

eer when you are unwilling to up the malt or hops in order to add some character to the beer. Britain has any number of very tasty low alcohol ales, but they differ to this attempt by Guinness because session ales in Britain are designed to be tasty and low strength, while Guinness appeared to have merely removed the alcohol but left everything else much the same. Secondly it pissed me off that the mid strength was almost the very same price as full strength beer despite the reduction in excise that Guinness had to pay on the production of these beers. This is nothing new of course - a bottle of entirely alcohol free beer is the same price as normal beer in Irish pubs, but clearly Guinness have carried out expensive and extensive market research to establish a demand for this type of beer and perhaps might have considered making it a little cheaper to attract those who might be happy to drink this type of beer and drive home afterwards. Finally, despite the lack of satisfaction I derived from these beers, I am very happy to see them on the market. As I said, it is likely much market research pointed to a consumer demand for low strength beer, which is a wonderful thing as it can only inevitably lead to the availability of tasty bitters and mild in Ireland. Or maybe I'm just getting carried away.

Friday, January 9, 2009

Worth the wait

I offer my sincere thanks and apologies to Velky Al for the gift of this bottle of wonderful Primator 16. My thanks because a beer given by a discerning beer lover is certain to be well researched and it was very kind of him to think of me during his visit to Ireland, but I must apologise for allowing it to languish in my beer fridge for so long. But that's how thing roll at the Black Cat Brewery; beers often disappear into the back of cupboards and fridges where they sit for an indefinite period of time, but they are never far from my thoughts. I just need the right occasion to enjoy them. On this cold night, weary after a game of squash, and sitting before a roaring (gas) fire the time seemed right. I have little experience with this type of beer, but my memories of a visit to Prague were vividly brought to the fore when I stuck my nose in the glass. It doesn't smell like other lagers, the body is richer and very satisfying and there is no DMS to speak off which was the only prediction I made for this beer, thinking perhaps that a strong lager would be strong in all lager aspects. In fact it is smooth with almost cask like carbonation, understated hops and not much alcohol really - surprising given the 7.5% swimming around in the glass. The Beer Nut was also gifted a bottle of this tasty beer, but his encyclopaedic beer knowledge provides it a place in the beer family tree, which sadly I cannot do.

Thanks again Al. Hopefully someday I can return the favour.

Thursday, January 8, 2009

The Boil

A solid rolling boil is essential in the brewing of good beer. It is energy intensive and potentially dangerous but a brewer skimps on boil time or intensity at his/her own peril. The boil must be vigorous and rapid, generally not longer than an hour. The intensity of the boil can be judged by the amount of water evaporated, with a figure of at least 10% being considered the minimum required to achieve what needs to done during the boil. The chemistry involved in wort boiling is immensely complex but can but can be broken down into a number of relatively straight forward mechanisms that contribute to beer quality.

A solid rolling boil is essential in the brewing of good beer. It is energy intensive and potentially dangerous but a brewer skimps on boil time or intensity at his/her own peril. The boil must be vigorous and rapid, generally not longer than an hour. The intensity of the boil can be judged by the amount of water evaporated, with a figure of at least 10% being considered the minimum required to achieve what needs to done during the boil. The chemistry involved in wort boiling is immensely complex but can but can be broken down into a number of relatively straight forward mechanisms that contribute to beer quality.Alpha acid isomerisation

One of the most important roles of the boil brewers carry out is the production of bittering compounds form the isomerisation of hop alpha acids. Isomerisation is a chemical process which involves molecules being converted from one configuration to another. Alpha acids are dubbed iso-alpha acids once isomerised but they contain the same amount of atoms, merely in a different configuration. The isomerisation reaction is favoured by alkaline conditions with a pH of around 9 being optimal, but these conditions are never met during the boil and this explains the notoriously poor level of hop utilisation during the brewing process which rarely exceeds 40%. Wort becomes steadily more acidic during the boil due to the formation of break material so the extraction of bitte ring compounds becomes less efficient as the boil goes on. Along with specific pH conditions, magnesium or another divalent ion and a vigorous boil are required to carry out the isomerisation reaction. The gravity of the wort can further influence the isomerisation reaction with high gravity worts impeding the progress of the isomerisation step. The loss of precious bittering compounds is bad enough, but the brewer can expect to further lose what little bittering has been achieved through adsorption to yeast and filter material and also some will be scrubbed by Co2 production during fermentation.

ring compounds becomes less efficient as the boil goes on. Along with specific pH conditions, magnesium or another divalent ion and a vigorous boil are required to carry out the isomerisation reaction. The gravity of the wort can further influence the isomerisation reaction with high gravity worts impeding the progress of the isomerisation step. The loss of precious bittering compounds is bad enough, but the brewer can expect to further lose what little bittering has been achieved through adsorption to yeast and filter material and also some will be scrubbed by Co2 production during fermentation.

One of the most important roles of the boil brewers carry out is the production of bittering compounds form the isomerisation of hop alpha acids. Isomerisation is a chemical process which involves molecules being converted from one configuration to another. Alpha acids are dubbed iso-alpha acids once isomerised but they contain the same amount of atoms, merely in a different configuration. The isomerisation reaction is favoured by alkaline conditions with a pH of around 9 being optimal, but these conditions are never met during the boil and this explains the notoriously poor level of hop utilisation during the brewing process which rarely exceeds 40%. Wort becomes steadily more acidic during the boil due to the formation of break material so the extraction of bitte

ring compounds becomes less efficient as the boil goes on. Along with specific pH conditions, magnesium or another divalent ion and a vigorous boil are required to carry out the isomerisation reaction. The gravity of the wort can further influence the isomerisation reaction with high gravity worts impeding the progress of the isomerisation step. The loss of precious bittering compounds is bad enough, but the brewer can expect to further lose what little bittering has been achieved through adsorption to yeast and filter material and also some will be scrubbed by Co2 production during fermentation.

ring compounds becomes less efficient as the boil goes on. Along with specific pH conditions, magnesium or another divalent ion and a vigorous boil are required to carry out the isomerisation reaction. The gravity of the wort can further influence the isomerisation reaction with high gravity worts impeding the progress of the isomerisation step. The loss of precious bittering compounds is bad enough, but the brewer can expect to further lose what little bittering has been achieved through adsorption to yeast and filter material and also some will be scrubbed by Co2 production during fermentation.

Colloidal stability

We all love bright haze free beer and this is one of the major reasons that wort boiling must be carried out properly. During the boil molecules called polyphenols stemming from malt and hops bind to the protein in the wort and form complexes that precipitate out of solution and comprise the hot break material. These processes can take up to 2 hours, but boils rarely exceed 90 minutes for reasons of economy. If the boil is not of sufficient duration to allow break formation, polyphenols and protein matter will persist into the beer and cause problems with clarity. After boiling, wort can contain up to 8000 mg/L of break material which is generally removed before the wort is fermented, though some brewers think that the break material provides additional nutrition for yeast and leave a degree of it in. Kettle finings such as carageenan moss is used to aid precipitation by binding the break material forming large flocs which fall from solution more efficiently than the break material would alone. It should be noted that specific doses of kettle finings are required to get maximum sedimentation and brewers carry out trials to determine the optimal dosage.

Sterilisation

The crushed malt that brewers mash in with is awash with unwanted and deleterious microorganisms such as bacteria and wild strains of yeast. The boiling of wort provides the very important role of sterilising the wort before fermentation lest the unwanted microbes present in the freshly produced wort wreak havoc with the fermentation process.

Enzyme inactivation

The fresh wort drawn from the mash tun is a cocktail of active enzymes that have been hard at work during the mashing process. This is a cause of concern to the brewer who has no do

ubt carefully selected the grain bill and carried out the mash at a specific temperature with the intention of attaining desired characteristics mainly pertaining to body and residual extract. If mashing enzymes such as the amylases are permitted to continue what they do best in the wort, the residual sugars which the brewer fought to keep in the wort will be degraded and metabolised during fermentation. Beta galactosidase is an enzyme of concern because it breaks down dextrins and makes them accessible to the remaining amylases. This enzyme has been shown to survive mashing and is exploited by distillers - who do not boil their wort - to ensure maximum fermentables are available during fermentation. Distillery fermentations often drop down as low as .997 thanks to the activity of beta galactosidase, so brewers would be best served to stop this enzyme in its tracks before fermentation starts.

ubt carefully selected the grain bill and carried out the mash at a specific temperature with the intention of attaining desired characteristics mainly pertaining to body and residual extract. If mashing enzymes such as the amylases are permitted to continue what they do best in the wort, the residual sugars which the brewer fought to keep in the wort will be degraded and metabolised during fermentation. Beta galactosidase is an enzyme of concern because it breaks down dextrins and makes them accessible to the remaining amylases. This enzyme has been shown to survive mashing and is exploited by distillers - who do not boil their wort - to ensure maximum fermentables are available during fermentation. Distillery fermentations often drop down as low as .997 thanks to the activity of beta galactosidase, so brewers would be best served to stop this enzyme in its tracks before fermentation starts.Volatile Removal

The large plumes of steam that pour from the kettle during the boil carry out the important action of removing with it unwanted volatile compounds that would negatively impact on the flavour of the beer should they be permitted to stay in the wort. These compounds stem from the action of heat on hop constituents and also compounds present in the malt. Unpleasant, harshly bitter hop molecules are driven out in the steam along with dimethyl sulphide (DMS) which is present in lightly kilned malt. DMS is not a major factor during ale brewing because the slightly higher kiln temperature during the production of pale malt drives off most of the DMS. Lager malt has higher levels, but a slight DMS character is considered to be part of the style of European lagers so total elimination during the boil rarely occurs. An important practical consideration with respect to the removal of these compounds is to ensure that the kettle is not covered during the boil to prevent the volatile containing steam condensing and flowing back into the wort. Commercial kettles often contain a trap in the flue to prevent this from occurring.

Colour and flavour addition

The intense heat generated during boiling promotes various chemical reactions that contribute to the colour and flavour of the beer. Most of these are reactions involving sugars that are caramelised or complex with proteins in Maillard reactions to from dark compounds that influence beer colour. The degree of colour and flavour formation is influenced by the manner in which the heat is applied to the wort. Directly fired kettles can create large amounts of these compounds because of the high temperatures at the point of heat application. This scorching often adds specific character to the beer, but can problem because the scorched wort material may adhere to the base of the kettle and prevent effective heat transfer. For this reason kettles must be cleaned throughly to prevent build up of debris on heating elements.

Monday, January 5, 2009

Clearly Problematic

Sulphur compounds are nasty things. Their presence is rarely welcome in beer, with perhaps the exception of small levels of dimethyl sulphide (DMS) in specific lager types. Hydrogen sulphide is another offender, being responsible for the smell of rotten eggs and the funkiness of primary fermentation. Yeast produce it at quite high levels during the frenzy of fermentation, but it is thankfully scrubbed from the beer by rapidly rising carbon dioxide. The classic exception to higher than normal levels of sulphur in beer is the 'Burton Snatch', famous in beer brewed with Burton water in the Midlands of England. It is caused by a very high sulphate concentration in the brewing water and has become a distinguishing feature of the style.

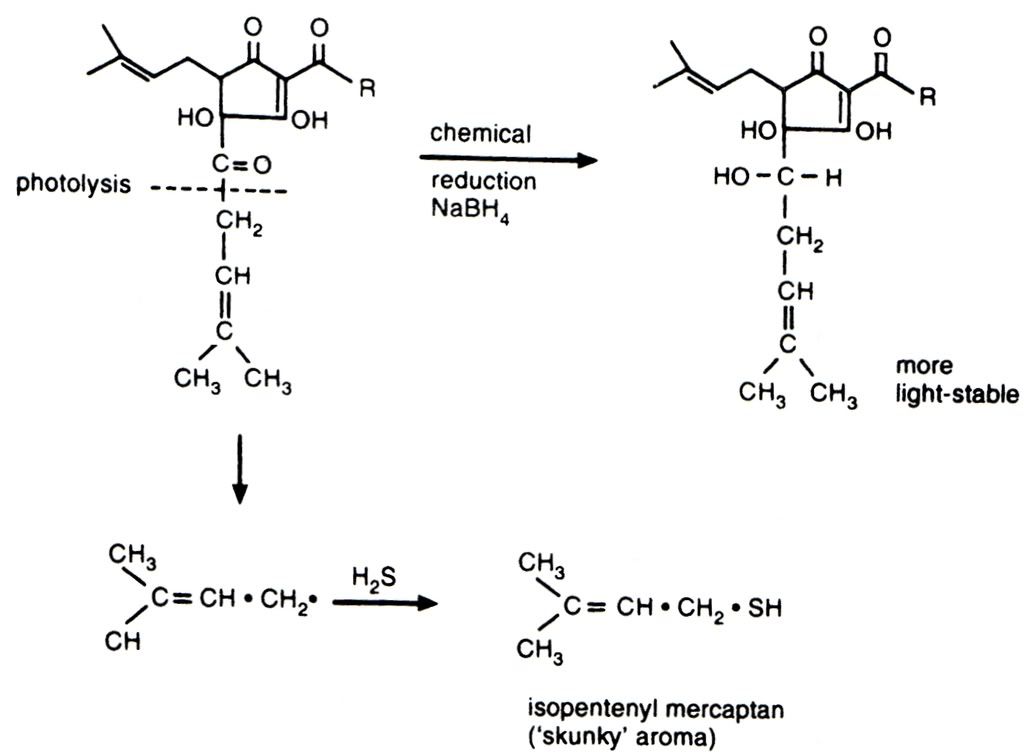

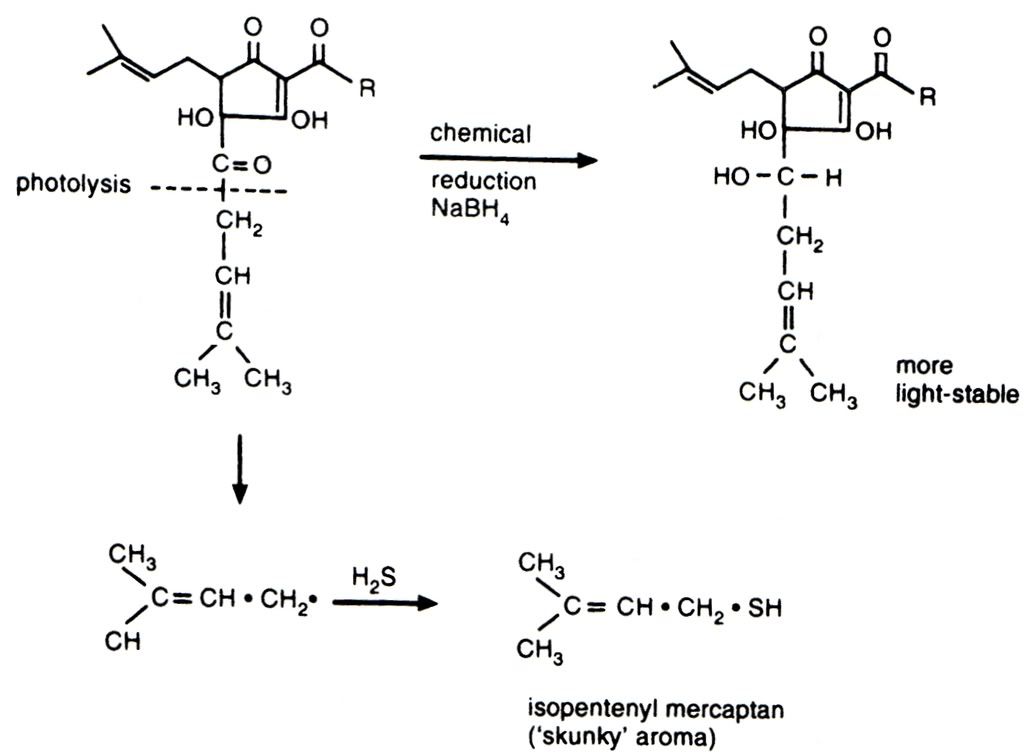

My personal sulphuric bugbear is the odour and flavour from light struck hops, more commonly known as skunking. It irritates me because it is the most easily preventable of all the invasive sulphur tints that plague beer - just stick the bloody beer in a brown bottle. The chemistry of skunking can be seen below. I love organic chemistry, but it's not for everyone and I am sorry for inflicting it on those who do not share my interest. The photolytic reaction to the left/down is the cause of my woes, the result of which is isopentyl mercaptan - the classic skunky smell. The top reaction running left to right is some clever brewing scientist's bright idea to prevent the breakdown of the hop alpha acid and remove the production of unpleasant sulphur compounds. These products are called reduced alpha acids (reduction is a chemical process involving the donation of electrons to a molecule). These reduced compounds do not suffer from light strike and also have the added bonus of providing more bitterness than an equivalent measure of standard alpha acids. Curiously they also promote far better foam stability, but at the risk of the foam looking rocky and artificial.

compounds. These products are called reduced alpha acids (reduction is a chemical process involving the donation of electrons to a molecule). These reduced compounds do not suffer from light strike and also have the added bonus of providing more bitterness than an equivalent measure of standard alpha acids. Curiously they also promote far better foam stability, but at the risk of the foam looking rocky and artificial.

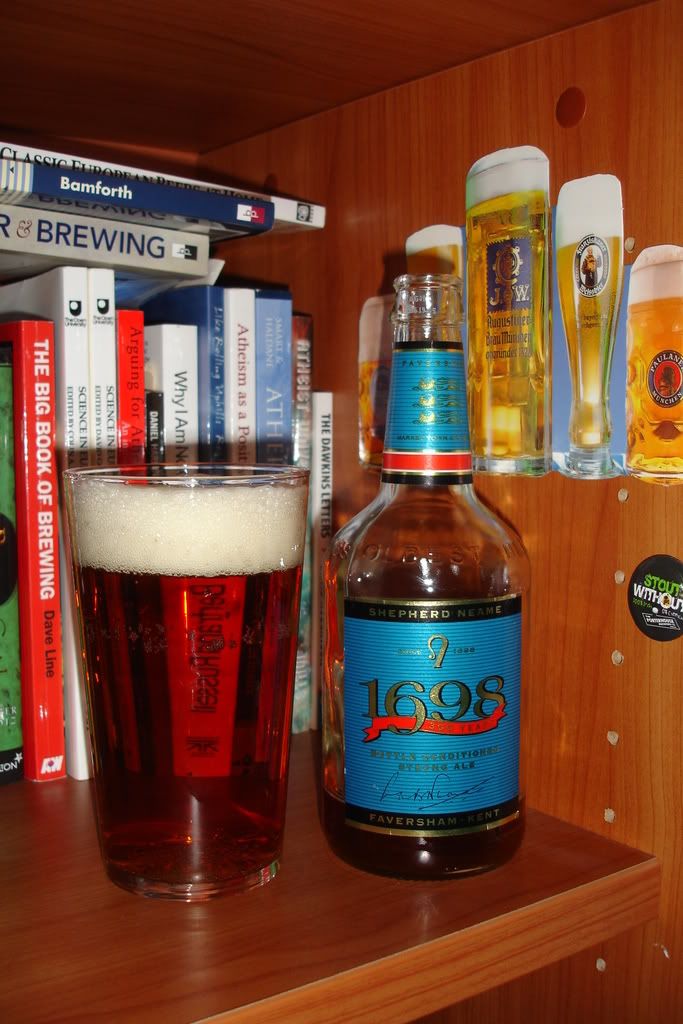

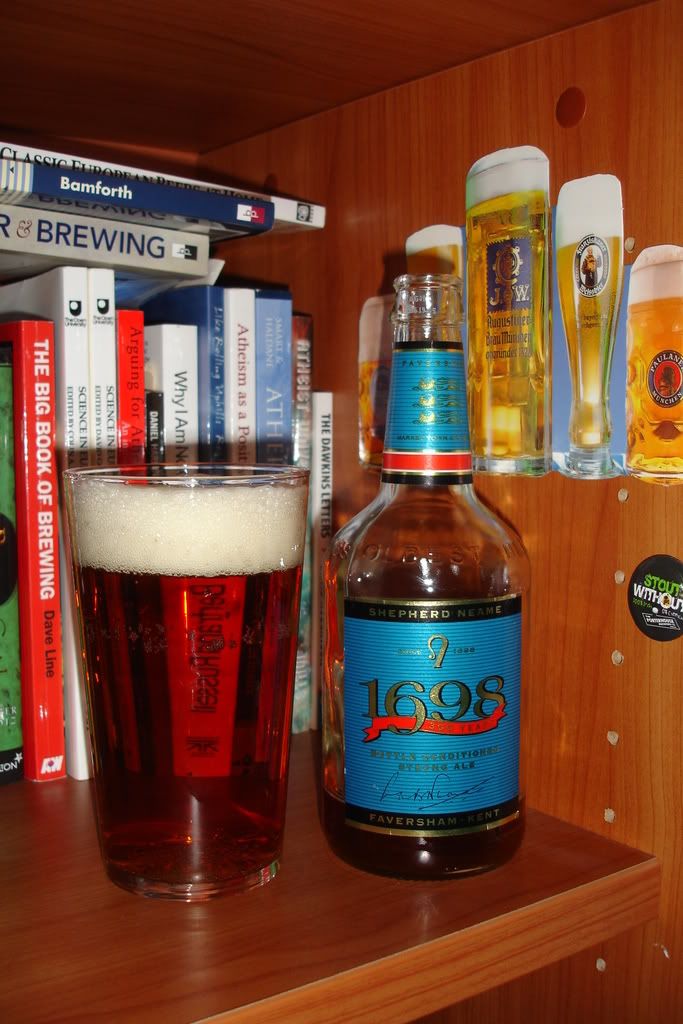

I stopped buying beer in clear bottles quite some time ago because of the unpleasant smell and flavour it suffers from. This is shame because there are quite a number of good beers sold in clear glass bottles. The difference between a beer in its intended state and the sorry condition it reaches us in clear glass has been highlighted to me on a number of occasions. The first was Marston's Old Empire IPA, an unremarkable beer in the bottle that tastes just like every other light struck beer, but a pint of it from cask at th e GBBF proved entirely different and not just because of the cask/bottle divide. The most striking difference I have experienced was Bishop's Finger from a bottle that had been kept under wraps away from mischievous photons. It is a true strong malty richly hopped ale in this condition, but tastes like every other ale in a clear bottle when exposed to light. Happily I can say the same for this particular bottle of 1698 because the people at CAMRA must have kept it from the light during processing, and I, hopeful that they had done so, stashed it in the cupboard in the hope that it might be free from light struck off flavours. Thankfully it has not a hint of skunking. Instead it is a wonderful strong ale with full, sticky body and satisfying minerally English hops. I do not know why Shepherd Neame put all their beer in clear bottles. It seems crazy to me, especially with the generous hopping that is typical in most of their ale.

e GBBF proved entirely different and not just because of the cask/bottle divide. The most striking difference I have experienced was Bishop's Finger from a bottle that had been kept under wraps away from mischievous photons. It is a true strong malty richly hopped ale in this condition, but tastes like every other ale in a clear bottle when exposed to light. Happily I can say the same for this particular bottle of 1698 because the people at CAMRA must have kept it from the light during processing, and I, hopeful that they had done so, stashed it in the cupboard in the hope that it might be free from light struck off flavours. Thankfully it has not a hint of skunking. Instead it is a wonderful strong ale with full, sticky body and satisfying minerally English hops. I do not know why Shepherd Neame put all their beer in clear bottles. It seems crazy to me, especially with the generous hopping that is typical in most of their ale.

As an aside, in the above photolytic chemical reaction it is the presence of the oxygen atom and double bond that is responsible for light strike. Oxygen is very electronegative which means it really pulls on the electrons in the bond with the lower carbon atom. This weakens the bond and allows the lower fraction of the molecule to be cleaved off by an energetic photon. This same electronegativity is responsible for all life on earth in as much as it is the reason why a small molecule like water is a liquid at ambient temperature. So I'm left with a dilemma; all life on earth or skunk free beer?

My personal sulphuric bugbear is the odour and flavour from light struck hops, more commonly known as skunking. It irritates me because it is the most easily preventable of all the invasive sulphur tints that plague beer - just stick the bloody beer in a brown bottle. The chemistry of skunking can be seen below. I love organic chemistry, but it's not for everyone and I am sorry for inflicting it on those who do not share my interest. The photolytic reaction to the left/down is the cause of my woes, the result of which is isopentyl mercaptan - the classic skunky smell. The top reaction running left to right is some clever brewing scientist's bright idea to prevent the breakdown of the hop alpha acid and remove the production of unpleasant sulphur

compounds. These products are called reduced alpha acids (reduction is a chemical process involving the donation of electrons to a molecule). These reduced compounds do not suffer from light strike and also have the added bonus of providing more bitterness than an equivalent measure of standard alpha acids. Curiously they also promote far better foam stability, but at the risk of the foam looking rocky and artificial.

compounds. These products are called reduced alpha acids (reduction is a chemical process involving the donation of electrons to a molecule). These reduced compounds do not suffer from light strike and also have the added bonus of providing more bitterness than an equivalent measure of standard alpha acids. Curiously they also promote far better foam stability, but at the risk of the foam looking rocky and artificial.I stopped buying beer in clear bottles quite some time ago because of the unpleasant smell and flavour it suffers from. This is shame because there are quite a number of good beers sold in clear glass bottles. The difference between a beer in its intended state and the sorry condition it reaches us in clear glass has been highlighted to me on a number of occasions. The first was Marston's Old Empire IPA, an unremarkable beer in the bottle that tastes just like every other light struck beer, but a pint of it from cask at th

e GBBF proved entirely different and not just because of the cask/bottle divide. The most striking difference I have experienced was Bishop's Finger from a bottle that had been kept under wraps away from mischievous photons. It is a true strong malty richly hopped ale in this condition, but tastes like every other ale in a clear bottle when exposed to light. Happily I can say the same for this particular bottle of 1698 because the people at CAMRA must have kept it from the light during processing, and I, hopeful that they had done so, stashed it in the cupboard in the hope that it might be free from light struck off flavours. Thankfully it has not a hint of skunking. Instead it is a wonderful strong ale with full, sticky body and satisfying minerally English hops. I do not know why Shepherd Neame put all their beer in clear bottles. It seems crazy to me, especially with the generous hopping that is typical in most of their ale.

e GBBF proved entirely different and not just because of the cask/bottle divide. The most striking difference I have experienced was Bishop's Finger from a bottle that had been kept under wraps away from mischievous photons. It is a true strong malty richly hopped ale in this condition, but tastes like every other ale in a clear bottle when exposed to light. Happily I can say the same for this particular bottle of 1698 because the people at CAMRA must have kept it from the light during processing, and I, hopeful that they had done so, stashed it in the cupboard in the hope that it might be free from light struck off flavours. Thankfully it has not a hint of skunking. Instead it is a wonderful strong ale with full, sticky body and satisfying minerally English hops. I do not know why Shepherd Neame put all their beer in clear bottles. It seems crazy to me, especially with the generous hopping that is typical in most of their ale.As an aside, in the above photolytic chemical reaction it is the presence of the oxygen atom and double bond that is responsible for light strike. Oxygen is very electronegative which means it really pulls on the electrons in the bond with the lower carbon atom. This weakens the bond and allows the lower fraction of the molecule to be cleaved off by an energetic photon. This same electronegativity is responsible for all life on earth in as much as it is the reason why a small molecule like water is a liquid at ambient temperature. So I'm left with a dilemma; all life on earth or skunk free beer?

Labels:

1698,

Beer Review,

DMS,

Hops,

Lightstrike,

Skunking,

Technical

Thursday, January 1, 2009

Malto Cumulus

A new year and what a beer to start it with. My wife and I took off to the house of a friend for the New Year celebrations along with a bottle of Duvel Special Edition Tripel Hop for sharing. These big beers in big bottles are always best shared with mates I find, and I am glad when a suitable event comes around that warrants the opening of a much anticipated beer. Once I had braved the cat's swift reflexes and razor sharp claws in extricating the bottle from his person we headed a few miles across the city and settled in with Indian food and other lovely treats. I decided to wait until after dinner to pop the cork on this beer, but it would have made very short work indeed of the spicy food we enjoyed. It pours almost the same colour of classic Duvel but the foam was more dense - inconceivably so, quite an achievement which anyone who has hastily poured a glass of classic Duvel will attest to. An arm's length sniff of the glass explains why the foam resembles dense cumulus cloud; it is hopped to within an inch of its life and hop alpha acids add superb support t

A new year and what a beer to start it with. My wife and I took off to the house of a friend for the New Year celebrations along with a bottle of Duvel Special Edition Tripel Hop for sharing. These big beers in big bottles are always best shared with mates I find, and I am glad when a suitable event comes around that warrants the opening of a much anticipated beer. Once I had braved the cat's swift reflexes and razor sharp claws in extricating the bottle from his person we headed a few miles across the city and settled in with Indian food and other lovely treats. I decided to wait until after dinner to pop the cork on this beer, but it would have made very short work indeed of the spicy food we enjoyed. It pours almost the same colour of classic Duvel but the foam was more dense - inconceivably so, quite an achievement which anyone who has hastily poured a glass of classic Duvel will attest to. An arm's length sniff of the glass explains why the foam resembles dense cumulus cloud; it is hopped to within an inch of its life and hop alpha acids add superb support t o foam. The dry hop aroma is pungent, the likes of which I haven't smelled since the home brew produced by the brewers at ICB where experimentally heroic amount of hops are often added to IPAs and pale ales. Spicy hops explode in the mouth, swifty followed up by glorious alcohol warmth that lingers all the way down to the belly, the combination of which gives a long, long satisfying finish. Intense bitterness also hangs around for a while too, but the immense malt body matches it perfectly and prevents it from dominating. I can't help but draw comparisons with American double and imperial IPAs and the like because they share many traits. The 9.5% abv is right up there with this type of beer and the immense use of hops and malt is similar too, but the Duvel strikes me as a far more refined beer, which while very heavily hopped doesn't have the rough edges that so many big hitter imperial IPAs have. It is a superb beer overall and well suited to a time of celebration. Sadly it isn't available in Ireland - I had to source this from England, but I hope it turns up soon because I want some more.

o foam. The dry hop aroma is pungent, the likes of which I haven't smelled since the home brew produced by the brewers at ICB where experimentally heroic amount of hops are often added to IPAs and pale ales. Spicy hops explode in the mouth, swifty followed up by glorious alcohol warmth that lingers all the way down to the belly, the combination of which gives a long, long satisfying finish. Intense bitterness also hangs around for a while too, but the immense malt body matches it perfectly and prevents it from dominating. I can't help but draw comparisons with American double and imperial IPAs and the like because they share many traits. The 9.5% abv is right up there with this type of beer and the immense use of hops and malt is similar too, but the Duvel strikes me as a far more refined beer, which while very heavily hopped doesn't have the rough edges that so many big hitter imperial IPAs have. It is a superb beer overall and well suited to a time of celebration. Sadly it isn't available in Ireland - I had to source this from England, but I hope it turns up soon because I want some more.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)